Maybe I ought to say something to establish my Woody Allen credentials: I have long admired, even cherished, his work, the high points of which I take to be Manhattan (1979) and Stardust Memories (1980). Sleeper still seems fresh after more than 30 years, and his two stark, little chamber dramas from the late 1980s—September and Another Woman—are vastly better than their repute. Alice, his whimsical fantasy about the effects of a Chinatown herbalist on an affluent hausfrau, seemed awfully frivolous back in 1990, yet has grown richer with the years; it remains Allen’s most gorgeous film in color. By contrast, Hannah and Her Sisters doesn’t hold up well: despite the brilliance of a few performers, the film sags under the weight of exposition, and visually, it resembles mud.

After Allen’s breakup with Mia Farrow, which yielded the wonderfully brutal Husbands and Wives, his movies became increasingly thin. True, there were some terrible pictures with Farrow: Shadows and Fog, Crimes and Misdemeanors, the Allen segment of New York Stories. Yet one could hold out hope, even as the films grew worse, that the writer-director would again produce inspired work. I enjoyed most of Everyone Says I Love You, particularly a scene in which Julia Roberts, with a straight face, makes a speech about the Allen character’s “astonishing sexual technique.” On the heels of this sweet-natured musical came the vituperative Deconstructing Harry, and after that I gave up on Allen for a time. I returned for Sweet and Lowdown, a film I hated to such a degree that it kept me away from Allen films for years—until last spring when, for some reason, I borrowed the Small Time Crooks tape from the public library. Although cringingly puny for most of the way, Small Time Crooks does have Tracey Ullman, and there’s a wistfully comic, lovely scene of Allen and his contemporary Elaine May strolling the boardwalk together, bantering as if they’d known each other all their lives. That one bit between them was so good, I wished Allen would’ve followed it somewhere, listened to it.

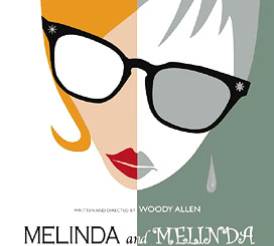

Perhaps because I hadn’t seen Anything Else or Hollywood Ending, I could luxuriate in the whispers that his newest film, Melinda and Melinda, marked a return to form—or close enough. Certainly, Allen has assembled an intriguing cast, including four quite gifted young actresses: Chloë Sevigny, Amanda Peet, Radha Mitchell, and the too-long underrated Brooke Smith. The idea behind the film—a pair of alternate takes on more or less the same story, one tragic, one comic—would seem fertile ground for the Allen sensibility.

Last week, after several months of keen anticipation and—yes—hope, I finally saw Melinda and Melinda.

It is awful.

The saddest thing about this bankrupt picture is that it renders hope for Allen finding a way out of his post-Mia aesthetic quagmire impossible. Even in such slender reeds as Manhattan Murder Mystery or A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, a viewer could reliably count on engaging performances from an Allen film or the visual pleasures in his uses of the frame.

That Melinda and Melinda is the first Allen film I have seen that is poorly acted doesn’t entirely account for what a despairing failure the movie turns out to be. Although the colors and lighting are warm, the shots are uninteresting, a shock given that Vilmos Zsigmond was the cinematographer. But now comes the truly odd part: even Allen’s usually impeccable taste in jazz standards has deserted him. The soundtrack, except for a snippet of pizzicato from a Bartok string quartet, is as boring as Allen’s unspeakable dialogue (about which, more in a moment). Allen chooses the stalest warhorses from the Ellington repertory: “Take the A Train,” “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore.” The abundance of Erroll Garner recordings used doesn’t help either. Although I like some of Garner’s final sessions from the 1970s, when he felt free enough to combine the harpsichord with conga drums in his arrangements, and to open up his piano playing into a wider, more symphonic palette, what we hear in Melinda and Melinda are his crabbed, ham-fisted, cluster assaults on the keyboard from the 1950s, an indiscriminate “style” that reduced each song to sounding the same.

That Melinda and Melinda is the first Allen film I have seen that is poorly acted doesn’t entirely account for what a despairing failure the movie turns out to be. Although the colors and lighting are warm, the shots are uninteresting, a shock given that Vilmos Zsigmond was the cinematographer. But now comes the truly odd part: even Allen’s usually impeccable taste in jazz standards has deserted him. The soundtrack, except for a snippet of pizzicato from a Bartok string quartet, is as boring as Allen’s unspeakable dialogue (about which, more in a moment). Allen chooses the stalest warhorses from the Ellington repertory: “Take the A Train,” “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore.” The abundance of Erroll Garner recordings used doesn’t help either. Although I like some of Garner’s final sessions from the 1970s, when he felt free enough to combine the harpsichord with conga drums in his arrangements, and to open up his piano playing into a wider, more symphonic palette, what we hear in Melinda and Melinda are his crabbed, ham-fisted, cluster assaults on the keyboard from the 1950s, an indiscriminate “style” that reduced each song to sounding the same.

Almost instantly, Allen’s tone deafness, even to irony, becomes apparent. He casts the playwright Wallace Shawn (whom Allen used for cruel good fun, as Diane Keaton’s “devastating” ex-husband, Jeremiah, in Manhattan) as a playwright who announces, in stymied earnest, “Audiences run to my comedies for escape.” Surely, there’s a joke here somewhere. Anyone who has ever attended a Shawn play or tried to read one (Aunt Dan and Lemon, for instance) knows that audiences are more inclined to run from his so-called comedies.

As he has done too often previously, Allen brackets this film with an utterly superfluous structure, rather than launching into a story straight out. The device here, an amicable squabble between two playwrights and their ostentatious acquaintances, uncomfortably evokes memories of My Dinner with Andre, co-written by and starring Wallace Shawn. Larry Pine, who looks a bit like a younger Andre Gregory, plays the opposing scribe, and their “argument” unfolds over the course of an evening at a bistro. The homage (if that’s what Allen intends) could have been fun or nostalgic or satirical, but Allen can no longer parody intellectual pitter-patter with the same brio he once had. As David Edelstein has pointed out, the wells are dry, and nowhere is this more starkly pronounced than in the dialogue spoken by the stage actress Stephanie Roth Haberle, the one woman at the bistro table. As the men go through the motions of debating tragedy’s supremacy over comedy or vice-versa, the overwrought Haberle asks: “Who can make such a judgment?” a line that might have seemed wittier in the Old Testament. At the end, when the two equally dreary versions of Melinda’s fate have dribbled away, leaving only an appalling impression, if any, Haberle patricianly enunciates, “No one definitive essence can be pinned down,” an observation that in a less morally indifferent universe than Allen’s would meet with a cream pie in the kisser.

The interlaced Melinda stories aren’t worth explicating, save to hear a few more lines of the film’s astounding dialogue, which the actors, with two exceptions, deliver as if they were reading aloud stage directions. Of the tragic Melinda, who claims to have spent time strait-jacketed at a state mental hospital in Illinois, a milieu of which Woody Allen undoubtedly would be well informed, someone says, “She’s in no bargaining position, especially when the facts are out.” We also learn that, courtesy of Jonny Lee Miller, who plays an unemployable “serious” actor so falsely intense he should have a heroin needle protruding from one arm, “Life has a malicious way of dealing with great potential.” Melinda herself states, “I don’t write operas, but my life has been one.” And Chloë Sevigny, still very much in the flower of her prime, is supposed to have had a career as a concert pianist: “Those days,” she confesses, “have vanished with a lost chord.”

The interlaced Melinda stories aren’t worth explicating, save to hear a few more lines of the film’s astounding dialogue, which the actors, with two exceptions, deliver as if they were reading aloud stage directions. Of the tragic Melinda, who claims to have spent time strait-jacketed at a state mental hospital in Illinois, a milieu of which Woody Allen undoubtedly would be well informed, someone says, “She’s in no bargaining position, especially when the facts are out.” We also learn that, courtesy of Jonny Lee Miller, who plays an unemployable “serious” actor so falsely intense he should have a heroin needle protruding from one arm, “Life has a malicious way of dealing with great potential.” Melinda herself states, “I don’t write operas, but my life has been one.” And Chloë Sevigny, still very much in the flower of her prime, is supposed to have had a career as a concert pianist: “Those days,” she confesses, “have vanished with a lost chord.”

The ghastliness of Allen’s writing, however, pales in comparison to the ineptitude of his direction. One minor example, then a major one. He has actually made a movie wherein three characters go to a recording session of the Bartok String Quartet No. 4 in order to cheer themselves up, and Allen fails to understand how bizarrely funny this is. How down and depressive must someone be for Bartok’s astringent harmonics to seem like a good time? It isn’t as if Woody were sending them to Papa Haydn or even to a Mozart Viola Quintet. He might as well have a character say, “Alone and helpless on Christmas morning, I comforted myself with Bartok’s Sonata for Solo Violin.” That would be less fatuous, at least, than what he gives us.

The real horror is that Allen has coaxed a bad performance from Radha Mitchell. I haven’t seen the studio films that Mitchell has done for paychecks, but I do know her extraordinary work in two difficult roles: Lisa Cholodenko’s High Art and in Marc Forster’s refreshingly savage dissection of fair weather friendship, Everything Put Together. Even in a small, underdeveloped role such as Johnny Depp’s abandoned wife in Finding Neverland, Mitchell submerges into character with authenticity and selflessness. She has tremendous range, none of which you’ll see in Melinda and Melinda. Woody Allen remakes Radha Mitchell in the image of a dirty Mia Farrow, one who speaks of having cultivated a taste for single malt Scotch (in the Illinois state hospital?) and delivering asides about her mother’s talent for interior decorating that are as loony as Geraldine Page’s obsessions over nearly the same subject in Interiors. With an unkempt mass of blond curls atop her smudgy face, and a peculiar tendency to lapse into a Southern accent in Melinda’s Gothic, hard luck revelations, Mitchell suggests Farrow and Jessica Lange locked in battle for the soul of Blanche DuBois. I cannot remember when last I saw a good actor give such a self-consciously tortured portrayal in a leading role, nor do I wish to.

Allen also mangles Vinessa Shaw, who shows up in a brief, thankless throwaway as a suicidal Republican. Sevigny looks lovely, yet she’s stiff as starch. Brooke Smith has her marvelous voice, and she’s luscious, either because or in spite of her advanced state of pregnancy. Smith, who was superb in Vanya on 42nd Street, uses her eyes to great effect; she conveys her humor and radiance with an ease that Allen’s atrocious lines do not.

Still, only two performers transcend this mess, and they appear too infrequently and to no real consequence. Chiwetel Ejiofor makes a late entrance as a pianist-composer named Ellis Moonsong. The handsome Ejiofor has beautiful skin tone. We hear almost nothing of Ellis’s music, yet Ejiofor’s bearing implies a fully lived interior life. He enables us to imagine what Moonsong might create. Better yet, there’s Amanda Peet, in recovery of the adroit comic timing that Nancy Meyers squashed in Something’s Gotta Give. Peet alone acquits well to what Allen tries to do. It helps that the one joke that doesn’t bomb belongs to her; she has great, instinctual rhythm, and she reinvents the trademark Woody mannerisms as if they were uniquely, organically her own. – NPT

March 21, 2005

You must be logged in to post a comment.